Writer and Data Visualisation: Shaza Al Muzayen

Editor: Sakina Mohamed

Designer: Ummul Syuhaida Othman

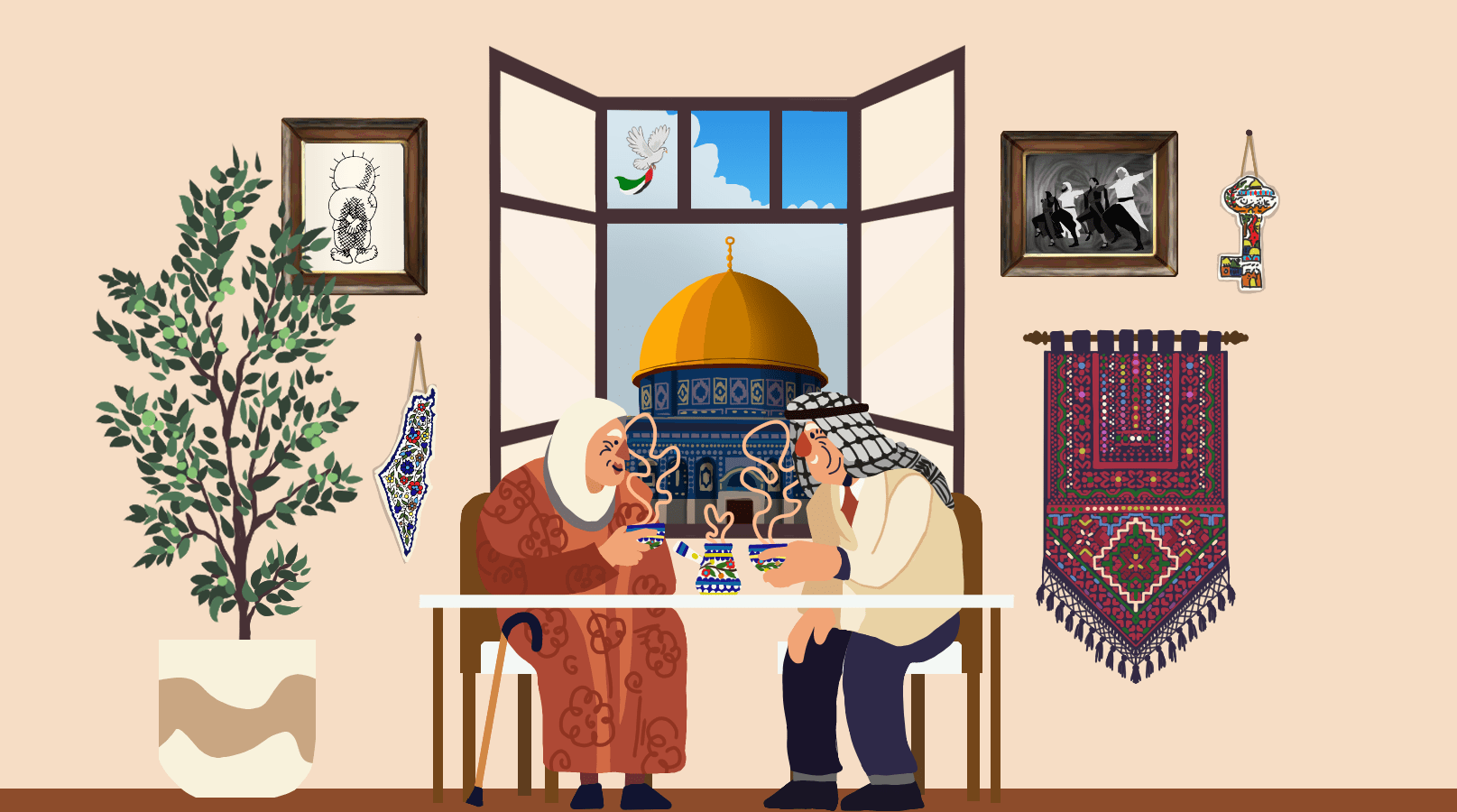

KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 29, 2025 (Bernama) -- Palestine is a land of symbols.

Some, like the keffiyeh, are widely recognised, having gained visibility through protests and global solidarity movements, while others remain lesser-known.

Every one of these symbols tells a story, reflecting the deep historical and cultural ties Palestinians have to their land and ongoing struggle for statehood.

In observance of the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, Garasi Bernama showcases eight symbols of Palestinian culture and heritage that capture the resilience, identity, and pride of the Palestinian people.

Digital Illustration by

Ummul Syuhaida Othman/BERNAMA

Many Palestinians carry old, iron keys with them, some wearing it on their necklace – but these are not jewellery. Rather, they’re a potent symbol of their right to return.

These were keys to the homes of 700,000 Palestinians who were forcibly displaced since the 1948 Nakba. This event was a catastrophic expulsion that began a relentless, ongoing struggle for their homeland.

Many of them carried their keys with them in the belief they would soon return. Similar scenes unfolded during the Naksa of 1967 and continue in the current genocide being committed in Gaza by Israel.

As linguist and researcher Dr Aladdin Assaiqeli notes, these keys emerged from the first days of the Nakba as “witnesses” – proof that Palestinians had homes in pre-1948 Palestine, even as many of those houses were demolished, renamed, or covered up in an attempt to erase them.

For Palestinians, the key is inseparable from the principle of the right of return. Enshrined in UN General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 194 (III) of 1948, this right affirms that refugees displaced during the Nakba and their descendants are entitled to return to their homes or receive restitution.

This can be seen through UNGA’s Resolution 3236, which “Reaffirms also the inalienable right of the Palestinians to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced and uprooted, and calls for their return.”

Israel has consistently refused to recognise this right. Instead, it took measures to prevent Palestinian return. A key instrument in this denial is the Absentees' Property Law of 1950, still used today by Israel to lay claim to Palestinian land that had been forcibly abandoned during the Nakba and the Naksa.

The law also enabled for the legalised looting of Palestinian belongings. Furniture, money and other household items were seized and placed under Israel’s Development Authority. The Israeli National Library holds nearly 8,000 books stolen from Palestinian homes during the Nakba.

In refugee camps and protests, replicas of these keys often appear on walls, monuments, and banners. One of the most striking examples is the “Key of Return” sculpture at the entrance of Aida Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. Installed in 2008, the massive steel structure spans the width of the camp’s gate, which has been built to resemble an old lock.

Passed down through generations, the key embodies both memory and resistance, defying time and what Assaiqeli calls “Israel’s systematic pursuit of Palestinian memoricide”. They stand as symbols of expulsion, but also of endurance - a reminder that the forced exile of Palestinians is not acceptance, and that the right of return remains unbroken despite the passage of decades.

This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.The “Key of Return” sculpture at the entrance of Aida Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. Installed in 2008, the massive steel key spans the camp’s gate, built to resemble an old lock. (Photo: Jj M Ḥtp)

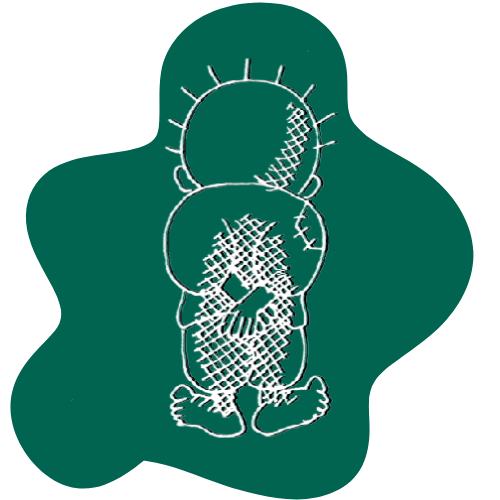

This drawing of a ten-year-old refugee boy with his back turned, arms crossed behind him is often seen during rallies in support of Palestine.

Spiky-haired, barefoot, and dressed in tattered clothes, Handala is one of Palestine’s most recognisable icons. He was created by the late Palestinian political cartoonist Naji al-Ali in 1969, and made to embody the innocence stolen from children of the Nakba and the determination of a people who refuse to surrender.

Handala is permanently frozen at the age of ten – the same age al-Ali was when he and his family were forcibly displaced from their village of al-Shajarah during the Nakba.

The name Handala is derived from the handhal, a desert plant native to the Levant with deep roots and bitter fruit. Known for its resilience, the plant grows back no matter how often its roots are cut. These qualities of bitterness and endurance became defining traits of Handala himself.

Al-Ali explained that Handala would remain a child until Palestinians regained their homeland, at which point he would begin to grow again. His turned back symbolises both rejection of injustice and refusal to compromise until liberation is achieved.

As scholar Orayb Aref Najjar observes, Handala also functions as a figure of witness and memory, representing not only displacement and loss but also the enduring Palestinian insistence on justice.

Naji al-Ali was assassinated in London in 1987. Yet the legacy of Handala has only grown stronger.

The figure has been invoked in global solidarity movements. In July 2025, the Freedom Flotilla’s ship Handala sailed in defiance of the Israeli naval blockade of Gaza. Activists chose the name to evoke his legacy of defiance, exile, and the hope of return.

Over the years, Handala has grown beyond the cartoon strips that first introduced him. He is graffitied on the separation wall between Israel and the West Bank, reproduced on protest posters, and shared across social media worldwide. In every form, Handala continues to remind the world of Palestine’s unfinished struggle for justice.

For now, however, he keeps his back turned, still waiting for the day when the people and land of Palestine are free.

The keffiyeh, or kufiya, is a traditional square cotton scarf worn across the Middle East, originally by farmers and villagers for protection against the sun and dust.

In Palestine, however, it came to signify much more than practical attire.

Before the end of the British Mandate, it was mainly associated with Bedouin men. According to dress historian Wafa Ghnaim, that changed during the 1936-1939 Arab Revolt against British colonial rule, when Palestinians of all social classes - Bedouin, villagers, and townsmen alike - adopted the keffiyeh as a symbol of unity, resistance, and nationalism. This created a uniform image of solidarity that even British soldiers could not ignore.

The keffiyeh’s status as an emblem of Palestinian struggle deepened in the decades that followed. After the Nakba, it became closely linked to the feda’iyiin (guerrilla fighters) and later to the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). Images of Yasser Arafat with the keffiyeh draped across his shoulder turned it into a visual shorthand for Palestinian nationalism.

(Photo: Özlem K)

The keffiyeh’s symbolism, however, extends beyond politics.

The patterns woven into the black-and-white Palestinian keffiyeh have been interpreted in different ways. The fishnet pattern evokes the sea, and for some, collectivism. The bold lines along the keffiyeh are said to symbolise the trade routes that once crisscrossed historic Palestine or the walls that now enclose and restrict it. Along the borders, the oval stitches are often seen as olive leaves, recalling the tree that sustains Palestinian life and symbolises resilience and rootedness in the land.

Today, the keffiyeh is worn worldwide, becoming an emblem of Palestinian resistance and solidarity. But its popularity has sparked debates over appropriation and commodification. Cheap imports are mass-produced in China, while luxury brands like Balenciaga and Louis Vuitton have marketed costly “fashion” versions. In contrast, the Hirbawi factory in Hebron - the last remaining keffiyeh producer in Palestine itself – still produces them on long-serving mechanical looms, preserving not only a garment but also a piece of Palestinian heritage.

Israelis, too, have laid claim to the scarf, likening it to the sudra (a Jewish religious headscarf), and some pro-Israel fashion outlets have marketed it as a “sudra/keffiyeh”. At the same time, Palestinians and their allies wearing the keffiyeh have often been vilified as supporting terrorism. It has even been labelled “the 21st-century swastika”. In November 2023, three Palestinian students in Vermont wearing keffiyehs and speaking Arabic were shot, leaving one paralysed from the chest down.

The keffiyeh remains one of Palestine’s most enduring cultural icons. Whether worn in exile or carried at a march, it continues to tell the story of a people bound together by resilience, identity, and the land they refuse to abandon.

The Al-Aqsa Mosque Compound, also known as Al-Haram Ash-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary), lies at the heart of Jerusalem’s Old City. It is one of Islam’s holiest sites and also holds a sacred place in Christianity and Judaism.

Recognised by the gleaming golden dome that sits atop the Dome of the Rock (Masjid Qubbat as-Sakhra), the compound spans 144 dunams of land (14.4 hectares). It also includes the silver-domed Al-Qibly Mosque (also referred to as the Al-Aqsa Mosque), along with a network of prayer halls, courtyards, homes, and religious schools.

For Muslims worldwide, the compound is revered as the site of the Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) Isra’ and Mi‘raj – the miraculous night journey and ascension to heaven, believed to have taken place at the rock enshrined within the Dome of the Rock.

For Palestinians, however, its meaning extends beyond faith. It is a symbol of national identity, sovereignty, and belonging in a city where access to the compound and its mosques is often restricted.

Throughout modern history, the compound has been at the centre of a continuous political, religious and ideological struggle as Israel and Zionist settlers repeatedly attempt to assert authority and ownership over the site.

In August 1969, the Al-Qibly Mosque was targeted in an arson attack by Australian Zionist extremist Denis Michael Rohan. The fire seriously damaged the mosque and destroyed the nearly 800 year old Mimbar of Salah al-Din.

In September 2000, Ariel Sharon entered the compound accompanied with a heavily armed escort of some 1,000 Israeli police officers. The visit, intended to reaffirm Israeli control over the site, provoked mass protests and helped ignite the Second Intifada (also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada). By its end in 2005, over 4,000 Palestinians and nearly 1,000 Israelis had been killed.

Repeated incursions by illegal settlers under the protection of Israeli forces, alongside restrictions on Muslim worshippers – particularly during Ramadan – have turned the sanctuary into a recurring flashpoint.

The compound and its surroundings also face the growing risk of structural damage and collapse due to Israel’s ongoing “archaelogical” excavations beneath and around the site.

On October 22, 2025, the Jerusalem Governorate issued the latest warning on Israel’s continuous digging and tunnelling under the compound and its neighbouring areas.

Advisor to the Jerusalem Governorate, Marouf al-Rifai cautioned that "the excavations could cause the destruction of some Palestinian landmarks, such as historic homes and ancient schools, as well as affect the soil beneath Al-Aqsa Mosque, threatening the stability of its foundations.”

Tatreez, the traditional art of Palestinian embroidery, has been practised for centuries. Once an intimate craft of village women, it was traditionally used to embroider thobes (traditional dresses) and domestic accessories.

Before 1948, it was a marker of individuality. Thobes adorned with hand-stitched embroidery told the story of their wearer – her village, her social standing, her marital status.

As noted by Widad Kawar and Tania Tamari Nasir in Palestinian Embroidery: Traditional “fallahi” Cross-Stitch, a “knowing eye” could once identify a woman’s home village simply by the patterns on her dress. Patterns like the cypress, moon, and bird weren’t mere ornaments but living symbols of the landscape and daily life that shaped them.

Lina Barkawi wearing the thobe she handmade for her katib kitaab (nikaah) ceremony. (Photo: Lina Barkawi)

The artistry of tatreez has long been preserved through generations of women.

“The Palestinian dress is known for its embroidery and women have been making it for centuries,” says US-born Palestinian-Panamanian tatreez practitioner Lina Barkawi to Bernama. “Historically, women would share their knowledge and designs from mother to daughter within their villages.”

After the 1948 Nakba, tatreez shifted from a personal craft to a means of survival, as displaced women used their embroidery skills to support their families.

“There was a shift not just in what they embroidered, but why they embroidered. Before the Nakba, a woman would stitch a dress for herself, something to wear on special occasions,” said Lina. “After 1948, she no longer had that privilege. Many sold their thobes and began making smaller items like pillow covers and table runners to earn a living.”

As Iman and Maha Saca note in Embroidering Identities: A Century of Palestinian Clothing, the regional distinctions in tatreez gradually disappeared after 1948. In refugee camps, women focused on a shared Palestinian identity rather than village-specific styles, using new fabrics and simpler designs that reflected their current economic constraints.

During the First Intifada, when Israel banned the Palestinian flag, women stitched its colours – along with keys, doves, and the Dome of the Rock – onto their thobes. The resulting “Intifada dress” became a form of wearable resistance.

“Palestinian women chose to resist their occupier in a way that made sense to them: by using the tools that they had and they stitched very explicit designs on their dress that depicted Palestinian liberation and identity,” said Lina.

“They wore the (Palestinian) flag on their backs,” she continued. “If Israel wanted to remove the flag, they would have had to forcibly remove the dress from the woman’s body.”

But like many Palestinian cultural practices, tatreez faces growing threats. Economic hardship, displacement and the Gaza genocide have endangered the transmission of these skills.

Attempts at appropriation have also emerged. Israeli fashion designers have incorporated stolen Palestinian motifs into their collections, and even Miss Universe’s 2021 edition in Israel showcased contestants wearing Palestinian thobes as part of a ‘visit Israel’ campaign.

Yet in the face of this, the international community has re-affirmed the Palestinian origins of tatreez. In 2021, the United Nations cultural agency (UNESCO) added it to its Intangible Cultural Heritage List of Humanity.

There has also been a revival in the Palestinian diaspora in learning tatreez.

“There’s a surge of women in the diaspora now picking it up,” said Lina, who lives in the US and teaches tatreez and thobe-making online and in person. “We have roofs over our heads, food on our tables – the privilege and time to do it for ourselves. In that way, we preserve the art form.

In the end, tatreez is more than just fabric or pattern. It is an archive of Palestinian life and history recorded in thread. Through the hands of women, it endures: an act of creation that defies erasure, one stitch at a time.

Digital Illustration by

Ummul Syuhaida Othman/BERNAMA

Dabke, a traditional Levantine folk dance, is often performed at weddings, festivals, and cultural events. It is usually danced in a line or circle, with a leader (the lawweeh) at the front improvising steps, spins, and shouts while the rest of the group follows in rhythm.

In Palestine, dabke has always been more than entertainment – it is a collective expression of unity, joy, and survival. Its stomping steps can be traced back to rural communal practices, from compacting mud roofs to preparing the soil for planting, tying the dance to home-making and the land itself.

Over the decades, dabke has become a deeply political emblem. Following the 1967 war, as Palestinian national consciousness grew, the dance shifted from a rural social custom to a powerful symbol of identity and resistance.

In Raising Dust: A Cultural History of Dance in Palestine, Nicholas Rowe notes that dabke was soon adopted at political rallies, where slogans sometimes replaced music to sustain its rhythm, and where each stomp came to signify presence, steadfastness, and refusal to disappear.

This intertwining of art and resistance is captured in the Palestinian concept of sumud, or steadfast perseverance. As Hamdonah and Joseph (2024) explain, dabke embodies sumud not simply as a performance but as a way of life: an anti-colonial stance that insists “to exist is to resist”, passed from one generation to the next.

For Palestinians in the diaspora, dabke remains a way to protect and bind national identity. Dance groups have kept it alive through performances and social media, creating what Hamdonah and Joseph call “glocal” links between communities abroad and the homeland. Whether in refugee camps, cultural centres, or university stages, dabke endures as both joyful resistance and embodied storytelling.

The dance has also faced appropriation. Rowe points out that during the British Mandate, Zionist choreographers took dabke steps to construct what they promoted internationally as an “Israeli dance style”, seeking to root themselves in a land whose Indigenous culture they simultaneously sought to erase.

At the same time, dabke has gained international recognition. In 2023, UNESCO inscribed dabke on its List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, highlighting both its cultural depth and its living role in modern Palestinian identity.

For Palestinians everywhere, the pounding rhythm of dabke is more than music and movement. It is a reminder that even in displacement, their roots remain unshaken and that their identity, like the dance itself, is kept alive through community.

Photo: Shafiq Hashim/Bernama

The flag of Palestine, with its black, white, and green horizontal stripes and red triangle, is one of the most visible emblems of Palestinian national identity.

According to Palestine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates, its colours are traced back to the 13th-century Arab poet Safi al-Din al-Hili, who praised Arab warriors by saying: “White are our deeds, black are our battles, green are our fields, red are our swords.”

The Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA) notes that the same colours also came to symbolise dynasties and movements in Islamic history: black for the Abbasids, white for the Umayyads, green for the Fatimids, and red linked to the Khawarij and later the Hashemites and the Arab Revolt of 1916.

The flag in its current design was first adopted by leaders of the Palestinian National Movement in the late 1920s. It was declared the official flag of the Palestinian people by the PLO in 1964, and recognised as the flag of the State of Palestine in 1988.

For Palestinians under occupation, raising the flag has long been an act of defiance.

A demonstrator holds the Palestinian flag in front of burning tyres during a protest along the border between the Gaza Strip and Israel, in solidarity with the Jenin camp after Israeli military operations there killed at least nine Palestinians. (Photo: Mohammed Talatene/dpa)

After Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and its annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967, Military Order 101 banned and criminalised the display of “flags or political symbols”, including the Palestinian flag, without prior military authorisation. As the late Palestinian scholar Edward Said observed, even the colours of the flag were outlawed.

The prohibition was enforced most aggressively during the First Intifada (1987-1993), when Israeli soldiers regularly arrested people for carrying the flag and confiscated items bearing its image. Palestinians resisted by stitching the colours into clothing and embroidering them into tatreez. To display the flag, in that context, was to openly defy erasure.

A Palestinian man holding the flag of Palestine walks in front of Israeli soldiers during a protest. (Photo: Shadi Jarar'ah/APA Images via ZUMA Wire/dpa)

Restrictions have continued into the present. In January 2023, Israel’s National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir ordered the Palestinian flag banned from all public spaces, calling it a symbol of solidarity with terrorism.

The flag’s significance also extends into the international arena. In 2015, the UN General Assembly voted to allow it to be raised at UN headquarters alongside those of member states – a symbolic recognition of Palestinian nationhood, even as full membership remained out of reach.

Today, the Palestinian flag appears at marches from Kuala Lumpur to New York. It is waved in refugee camps and carried across diaspora communities, making it one of the most recognisable symbols of solidarity with Palestine worldwide.

Digital Illustration by

Ummul Syuhaida Othman/BERNAMA

The outline of historic Palestine is more than just a shape on a page. For Palestinians, it is a powerful reminder of home.

That map has long been contested by Israel. At the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, Zionist leaders presented their vision of Eretz Israel or “Land of Israel”, a map that went far beyond areas of actual Jewish settlement at the time. It was a bold claim that ignored the lived reality of Palestine: a land already inhabited and farmed by its people.

Against this backdrop, the historical map of Palestine became a counter-claim, a refusal to accept erasure. As Salman Abu-Sitta stresses in Atlas of Palestine: 1917–1966, the surveys and mapping carried out during the British Mandate proved that Palestine was not an empty desert, directly challenging the Zionist myth of “a land without a people for a people without a land.”

Through his atlases of villages, borders, and land ownership, Abu Sitta has preserved a detailed record of what was lost. He shows that although two thirds of Palestinians became refugees in 1948, 88 percent still live in historic Palestine or within 150 kilometres of it. This proximity, he argues, makes the map inseparable from the principle of return.

Where Abu Sitta links maps to the future of return, historian Walid Khalidi uses them to preserve the past. In All That Remains, he documented 418 villages destroyed or depopulated in 1948, complete with maps, photos, and village histories. His work turned cartography into testimony - proof that these communities once stood, and that their absence is not silence but dispossession.

As historian Nur Masalha points out in Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History, maps and place-names are also part of a longer story. Colonial and Zionist cartographies often erased or renamed Palestinian towns and villages, but families kept those names alive through oral history. For many Palestinians, remembering the map is a way of resisting erasure itself.

That struggle is far from over. In recent years, Israeli politicians have revived the idea of a “Greater Israel”, promoting maps that normalise annexation and permanent control from the river to the sea. To realise this vision, “Greater Israel” would consume the entirety of Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan, and also large parts of Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. For Palestinians, such expansionist ideals only sharpen the importance of holding on to their own historic map - not just as memory, but as a form of resistance.

-- BERNAMA